How slowing trade and rising barriers are redrawing the global economic map in 2025.

Introduction: A New Era of Friction

For much of the past half-century, globalization was taken for granted. Goods, data, and capital flowed with unprecedented ease, powered by free trade agreements and global supply chains that stitched continents together.

But in 2025, that world feels increasingly distant.

Trade growth — once the lifeblood of the global economy — has slowed to its weakest pace since the early 2000s. The World Trade Organization (WTO) projects global merchandise trade to rise by barely 2.3% this year, far below its 2010s average of over 5%.

From Washington to Beijing, Delhi to Brussels, nations are turning inward. Tariffs, export controls, and industrial subsidies are rewriting the rules of commerce. The pandemic, the war in Ukraine, and rising geopolitical tension have accelerated a new era: the era of strategic protectionism.

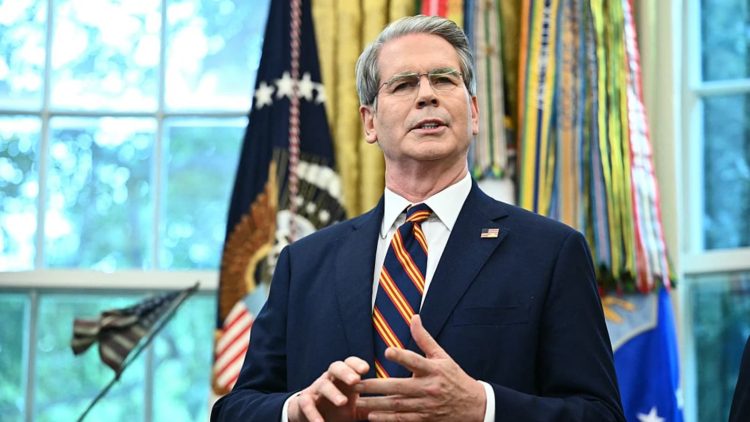

As IMF Chief Economist Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas warned earlier this year,

“We are witnessing not de-globalization, but a re-globalization — one defined by politics, security, and resilience rather than efficiency.”

1. The Weak Pulse of Global Trade

The slowdown is striking in both scale and scope.

After decades of expansion, trade as a share of global GDP has plateaued at around 58%, down from its 2008 peak of 61%.

Several factors explain this weakening pulse:

- Cooling global demand, as tighter monetary policy and inflation dampen consumption.

- Supply chain reconfiguration, with firms prioritizing security over cost.

- Trade fragmentation, driven by competing blocs and sanctions.

In Asia, export giants like South Korea and Taiwan have seen shipments of semiconductors and electronics decline sharply. Europe’s industrial heartland, Germany, is wrestling with weak orders from China. Even China — once the world’s export engine — is facing shrinking markets in the West due to geopolitical frictions and consumer fatigue.

The IMF estimates that trade tensions could shave 0.7 percentage points off global GDP growth in 2025–2026, a drag equivalent to wiping out the entire annual output of a mid-sized economy like the Netherlands.

2. The Rise of “Friendshoring” and the Fragmented Map

In response to rising risks, multinational corporations are redrawing their production maps.

The new keyword is friendshoring — shifting supply chains to politically aligned nations to reduce exposure to adversaries.

Apple is assembling iPhones in India. Japanese manufacturers are investing in Vietnam and Thailand. European carmakers are building battery plants in the United States to qualify for subsidies under Washington’s Inflation Reduction Act (IRA).

This diversification offers resilience, but it also fragments efficiency.

McKinsey’s Global Supply Chain Outlook 2025 finds that friendshoring can raise production costs by 10–20%, depending on the sector. For consumers, that translates into higher prices and slower innovation.

Yet policymakers argue it’s a necessary trade-off. “Security is the new efficiency,” said U.S. Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo in a May interview. “We can’t afford to depend on any single nation for critical technologies.”

3. The New Protectionism: Industrial Policy Returns

Protectionism today doesn’t always come with tariffs.

Instead, it wears the modern mask of industrial policy — subsidies, export controls, and state-directed investment.

The United States’ CHIPS and Science Act allocates $52 billion to domestic semiconductor manufacturing. The European Union’s Green Deal Industrial Plan channels hundreds of billions into renewable energy and electric vehicles. China continues to double down on self-reliance under its Made in China 2025 and Dual Circulation strategies.

These policies aim to build “strategic autonomy,” but collectively, they risk fragmenting global markets.

According to the WTO, the number of trade-restrictive measures introduced since 2019 has tripled, reaching a record 3,200 active restrictions as of mid-2025.

WTO Director-General Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala warned that “the world is entering a subsidy race with no referee — one where cooperation gives way to costly duplication.”

4. The China–U.S. Trade Rift: Structural, Not Cyclical

At the heart of the global slowdown lies the world’s most consequential trade relationship: China and the United States.

Despite periodic talks, the rivalry has deepened into a structural decoupling.

U.S. restrictions on advanced semiconductors and manufacturing equipment have cut deep into China’s high-tech exports. Beijing, in turn, has imposed curbs on critical minerals like gallium and graphite — key inputs for global battery and electronics production.

The result is a ripple effect through global supply chains.

Southeast Asian countries like Malaysia and Vietnam are benefiting from “China plus one” diversification, attracting new factories. But the broader cost is rising uncertainty, longer lead times, and reduced efficiency.

“Global trade has become politicized,” says Alicia García-Herrero, chief economist for Asia-Pacific at Natixis. “It’s no longer just about comparative advantage — it’s about comparative security.”

5. Europe’s Balancing Act

Europe finds itself caught between competing pressures.

On one side, it relies on the U.S. for security and technology cooperation. On the other, China remains its largest trading partner.

German exports to China fell 9% year-on-year in 2024, while energy costs and slow domestic growth continue to strain European manufacturers.

In response, the EU is exploring “de-risking” rather than “decoupling” — maintaining trade links while reducing dependency on critical materials and technologies.

The European Commission’s Economic Security Strategy emphasizes resilience through diversification and innovation. Yet analysts warn that without faster implementation, Europe risks losing competitiveness to both the U.S. and Asia.

“Europe needs an industrial awakening,” said Margrethe Vestager, EU Commissioner for Competition. “The world is not waiting for us.”

6. Emerging Markets: Between Opportunity and Exposure

For emerging economies, the trade realignment brings both opportunity and peril.

Vietnam, India, Mexico, and Indonesia are among the biggest winners, attracting record levels of manufacturing investment.

In 2024 alone, India’s exports of electronics surged 28%, while Vietnam became a key hub for textile and chip assembly.

Mexico’s proximity to the U.S. — and participation in the USMCA trade pact — has made it a prime beneficiary of nearshoring trends.

But others face turbulence. Commodity exporters like Brazil and South Africa are seeing weaker demand from China. Smaller developing nations risk being sidelined altogether, as investment flows concentrate in larger “friendly” markets.

“The world’s poorest countries are being left behind,” warns the World Bank’s latest Global Trade Monitor. “Their exports are growing at less than half the global average.”

7. The Technology Dimension: Chips, Data, and Digital Trade

Trade today isn’t just about goods — it’s about data, software, and semiconductors.

As economies digitize, control over these “invisible exports” has become a strategic priority.

The semiconductor industry, in particular, illustrates the new vulnerabilities of globalization.

A handful of firms — notably TSMC in Taiwan, Samsung in South Korea, and ASML in the Netherlands — dominate the world’s chip supply. Any disruption, whether political or environmental, has outsized ripple effects.

Data is another frontier. Nations are asserting “data sovereignty” through localization laws, requiring information to be stored within national borders. While this protects privacy and security, it also fragments the digital economy, undermining the global cloud infrastructure that powers AI and e-commerce.

The IMF estimates that digital fragmentation could cost the global economy up to $1.5 trillion annually by 2030 if left unchecked.

8. Inflation and the Consumer’s Burden

Trade friction doesn’t stay confined to boardrooms — it shows up in prices at the supermarket and electronics store.

Higher tariffs, disrupted logistics, and subsidy-driven inefficiencies are pushing costs upward.

In the United States, the IMF attributes roughly 0.4 percentage points of 2024 inflation to trade restrictions alone.

In Europe, energy and import costs remain elevated due to sanctions and supply shifts.

Developing countries are especially vulnerable, as imported food and fuel become more expensive amid currency depreciation.

Consumers are adapting through “value downgrading” — buying smaller, cheaper, or local alternatives. But the long-term risk is stagnation: if global trade remains sluggish, households everywhere will feel the squeeze.

9. Can Globalization Be Rewired?

Despite the headwinds, trade is not dying — it’s evolving.

New forms of globalization are emerging around technology, services, and regional networks.

The rise of digital trade — from streaming services to remote work and cloud software — is cushioning the decline in physical goods flows.

The WTO estimates that cross-border digital services exports grew 7.5% in 2024, even as merchandise trade stagnated.

Meanwhile, regional trade agreements are multiplying:

- The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) in Asia.

- The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) in Africa.

- And renewed interest in the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) among Pacific economies.

These frameworks suggest that globalization isn’t retreating — it’s rerouting.

10. Outlook: The Politics of Prosperity

The future of trade will depend less on tariffs and more on trust.

Geopolitical alliances, digital norms, and environmental standards are replacing traditional trade liberalization as the key forces shaping global commerce.

To sustain growth, nations will need to find balance — between protection and openness, resilience and efficiency, sovereignty and cooperation.

As WTO Director-General Okonjo-Iweala recently put it,

“The challenge is not whether we trade, but how we trade — and with whom we build our future prosperity.”

Globalization may never return to its 1990s heyday. But neither will it vanish.

In an uncertain world, the exchange of goods, ideas, and technology remains too vital — and too human — to be walled off forever.