How Tight Monetary Conditions Are Reshaping Markets, Credit, and Economic Power in 2025

Introduction: The World Enters a Liquidity-Constrained Era

For more than a decade after the 2008 financial crisis, the global economy was nourished by an unprecedented wave of liquidity. Central banks in advanced economies flooded markets with quantitative easing (QE), slashed interest rates to zero, and expanded balance sheets. Corporations borrowed cheaply, governments funded large deficits, and investors poured money into risk assets—tech equities, real estate, private equity, emerging markets, crypto.

That world has vanished.

Since 2022, central banks across the U.S., Europe, and parts of Asia have reversed course. Inflation forced them into the most aggressive tightening cycle in 40 years. Even as inflation moderates in 2024–2025, global liquidity remains tight because:

- policy rates are higher than pre-pandemic levels

- balance sheet reductions (QT) are ongoing

- banks are restricting credit

- financial regulations are tightening

- global savings patterns are shifting

A new macro landscape is taking shape: a structurally tighter liquidity regime. It is reshaping asset valuations, credit flows, capital allocation, economic power structures, and financial risk.

This article examines the dynamics of today’s liquidity squeeze, its drivers, the winners and losers, and the long-term implications for the global financial system.

1. Understanding the Global Liquidity Squeeze

1.1 What is global liquidity?

Global liquidity refers to the availability of credit, cash, and liquid assets across the world’s financial system. It is influenced by:

- central bank balance sheets

- interest rates

- cross-border capital flows

- bank lending behavior

- global reserve accumulation

- shadow banking activity

When liquidity is abundant, risk-taking increases. When liquidity tightens, borrowing costs rise, asset prices fall, and financial stress spreads.

1.2 How we moved from QE to QT

From 2008 to 2021:

- the Fed expanded its balance sheet from $900 billion to over $8 trillion

- the ECB grew from €1 trillion to nearly €9 trillion

- the Bank of Japan maintained near-zero rates and yield curve control

- China provided massive credit via state-owned banks

But after the 2021–2022 inflation surge, the trend reversed.

Today:

- the Fed is reducing its balance sheet by $95 billion per month

- the ECB is running down APP and PEPP holdings

- global M2 growth has turned negative in several economies

- banks face higher capital and liquidity requirements

This represents the most synchronized global liquidity withdrawal since quantitative easing began.

2. Why Liquidity Is Tightening Even as Inflation Falls

2.1 Central banks fear inflation’s return

Although inflation has cooled from peak 2022 levels, central banks are unwilling to return to the near-zero-rate world. They worry about:

- supply-side inflation (energy, geopolitics, supply chains)

- fiscal expansion

- wage gains

- the political unpopularity of inflation

This keeps policy rates higher for longer.

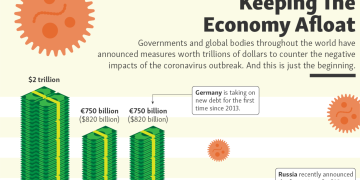

2.2 Fiscal policy is crowding out private borrowing

Governments are running large deficits due to:

- aging populations

- defense spending

- energy-transition subsidies

- industrial policy

- rising interest costs

To finance this, governments issue more bonds. Investors demand higher yields, pulling liquidity away from risk assets.

2.3 Banks are hoarding liquidity

Regional banking stress in the U.S. and credit deterioration in Europe and China have made banks more cautious. Banks are:

- tightening lending standards

- holding more reserves

- passing higher costs to borrowers

- reducing exposure to risky sectors (commercial real estate, small businesses)

A cautious banking system amplifies the liquidity squeeze.

2.4 The rise of macro uncertainty

Geopolitical tensions—from the Russia–Ukraine war to Middle East instability to U.S.–China rivalry—create volatility. Investors hold more cash, reduce leverage, and demand higher risk premiums.

3. The Financial Impact: Markets Under Pressure

3.1 Equities reprice in a high-rate environment

Low rates previously inflated valuations, especially in technology and growth sectors. A tight liquidity regime has reversed this dynamic:

- discount rates are higher

- earnings multiples compress

- unprofitable companies face existential risk

- dividends and cash flow matter more

- investors rotate from growth to value

Tech remains strong in AI-related earnings, but liquidity constraints create volatility.

3.2 Bond markets shift into a new equilibrium

The era of ultra-low yields is gone. Key trends:

- long-term yields remain elevated

- real yields rise

- term premiums increase

- sovereign debt sustainability becomes a concern

Governments cannot rely on cheap financing anymore.

3.3 Commodities rediscover financial relevance

Tight liquidity would normally depress commodities. But structural factors—energy underinvestment, supply-chain constraints, geopolitical risks—keep prices volatile and sometimes elevated. Commodities regain their role as:

- inflation hedges

- geopolitical risk hedges

- diversification assets

Energy and industrial metals benefit the most.

3.4 Tight liquidity pressures emerging markets

Emerging markets (EMs) are uniquely vulnerable:

- borrowing costs rise

- currency depreciation pressures foreign-denominated debt

- capital outflows intensify

- commodity-importing EMs face higher inflation

- geopolitical instability disrupts investment

Some EMs with strong reserves and commodity exports perform well (e.g., Brazil, Gulf states), but many face financing stress.

4. Credit Markets Under Strain

4.1 Corporate borrowing costs surge

Companies face:

- higher refinancing costs

- reduced access to bank loans

- tighter covenants

- declining investor appetite for junk bonds

Highly leveraged sectors—real estate, private equity, small-cap tech—are under severe pressure.

4.2 Commercial real estate (CRE) enters a crisis cycle

Remote work and high interest rates create a toxic combination for CRE:

- office occupancy remains low

- refinancing waves approach

- valuations fall 20–40%

- delinquencies rise

- regional banks face concentrated exposure

This sector represents a key systemic risk for 2025–2027.

4.3 Private credit grows—but becomes riskier

Private credit has exploded to more than $1.6 trillion globally, offering:

- higher yields

- flexible financing

- alternatives to bank loans

But tight liquidity exposes weaknesses:

- covenant-light loans

- borrower distress

- valuation opacity

- mismatched liquidity

Private credit could be a flashpoint in the next financial downturn.

5. How the Liquidity Squeeze Is Reshaping Economic Power

5.1 Capital flows shift toward safer economies

Countries with:

- stable institutions

- strong currencies

- deep capital markets

- credible central banks

- energy independence

attract the most capital. This benefits:

- United States

- Japan

- certain Northern European economies

- commodity-rich nations (Norway, Canada, Australia)

5.2 China faces structural liquidity challenges

China confronts several headwinds:

- property sector meltdown

- deflationary pressures

- declining foreign investment

- demographic decline

- household deleveraging

The People’s Bank of China must balance stimulus with financial stability, but structural constraints limit effectiveness.

5.3 The Global South becomes fragmented

Liquidity scarcity creates winners and losers among developing nations:

Winners:

- energy exporters

- large commodity producers

- politically stable economies

Losers:

- high external debt

- weak currencies

- import-dependent economies

- countries with political instability

Global inequality, both among and within nations, widens.

6. The Rise of Liquidity Sovereignty: A New Economic Paradigm

6.1 Nations prioritize financial autonomy

Governments now pursue liquidity sovereignty—the ability to secure domestic financing without relying on global capital markets. This includes:

- strengthening domestic bond markets

- developing local currency financing

- increasing FX reserves

- promoting bilateral currency swaps

- encouraging domestic savings

6.2 De-dollarization attempts accelerate—but face limits

Several emerging economies promote alternatives to the U.S. dollar. However:

- no other currency has comparable liquidity

- capital controls weaken alternatives

- political stability varies

- U.S. financial markets remain unmatched

The dollar remains dominant, but multipolarity is rising.

6.3 Sovereign wealth funds gain geopolitical influence

With liquidity scarce, sovereign wealth funds (SWFs) become powerful:

- investing in distressed assets

- supporting domestic industries

- shaping geopolitical alliances

The Saudi Public Investment Fund (PIF), Norway’s GPFG, and the UAE’s ADIA increasingly reshape global markets.

7. Long-Term Consequences of Tight Liquidity

7.1 A “slower but safer” global economy?

Tighter liquidity reduces excessive leverage, but also:

- slows growth

- lowers asset returns

- raises inequality

- increases default risk

The world shifts from rapid expansion to cautious stability.

7.2 Innovation and capital allocation change

Low rates previously fueled speculative innovation. Now:

- capital flows to profitable companies

- R&D must show clearer commercial potential

- speculative sectors shrink

- AI, biotech, green energy, and robotics remain strong due to structural demand

Innovation continues, but becomes more disciplined.

7.3 Financial crises become more likely—but also more contained

Tight liquidity increases the risk of:

- corporate defaults

- bank failures

- sovereign debt crises

- asset price crashes

But stronger capital rules and better regulation may help limit contagion.

8. Scenarios for the Next Three Years

Scenario 1: Prolonged Tight Liquidity (60% probability)

Central banks maintain high rates due to persistent geopolitical and supply-side pressures.

Result:

- slow growth

- weak equity returns

- credit stress intensifies

- EM volatility rises

Scenario 2: Liquidity Easing (25% probability)

A global slowdown forces rate cuts and renewed QE.

Result:

- risk assets rally

- bond yields fall

- but inflation risks return

Scenario 3: Global Financial Accident (15% probability)

A major event (CRE crisis, sovereign default, bank failure) triggers forced liquidity injection.

Result:

- central banks intervene

- markets rebound after shock

- debt restructuring cycles begin

Conclusion: Navigating a World Where Liquidity Is Scarce

The era of abundant liquidity is over. The world has entered a new financial environment dominated by:

- higher interest rates

- cautious central banks

- fragmented capital flows

- tighter credit standards

- slower economic growth

- rising geopolitical instability

For investors, companies, and governments, this new landscape requires a fundamental shift in strategy. Survival and success depend on:

- conservative leverage

- robust liquidity buffers

- strategic long-term planning

- disciplined capital allocation

- geopolitical awareness

In this new era, liquidity is not simply a macroeconomic variable—

it is the new currency of global power.